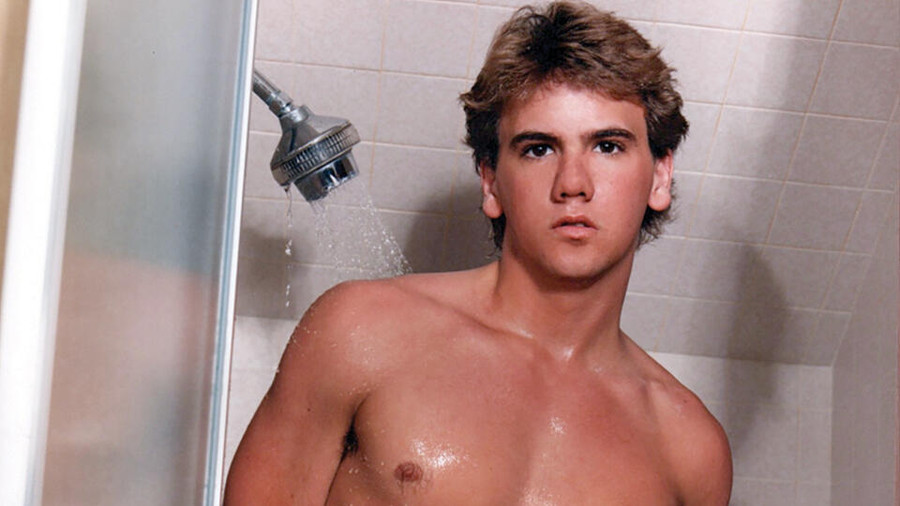

Doug Probst is eager to evangelize about his newly published memoir chronicling a remarkable life story that includes a second identity as Shawn Mayotte, notable beefcake star of all-male adult films and pinup magazines throughout the 1980s. But his eagerness is not simply about selling books. Probst is on a particular mission and he is careful, more than once, to steer our conversation back to it.

Right at the top of the acknowledgments of “Mayotte: The Musings of a Narcissist, A Survivor’s Story” is the following passage: “This book is dedicated to all of the children in the world who have suffered physical and sexual abuse. I know what it’s like to cry out in pain and no one hears you. I listened. I heard you. There will be no more suffering. I also dedicate this book to everyone who died of AIDS and are now suffering and dying from COVID-19. But I especially want to remember my friends who died on the streets of Long Beach from a virus that had no name yet. I’ll never let the world forget you.”

I knew almost everybody who was nobody — boys who were just walking down the street and got asked to be in films, I knew ’em all.

Probst may be many years removed from his time as a sex worker — he has long since transitioned to a notable career in the music industry — yet he can easily rattle off the names of his old colleagues, accompanied by a startling litany of minute details, from the style of the clothes one wore the first time Probst crossed paths with him to the weather on the afternoon of what turned out to be the last time he ever saw another. Probst remembers; he survived. He survived a torrent of childhood abuse and then survived the plague years. He is determined to be a voice for the voiceless and to ensure that the names of his friends lost to AIDS and addiction are not forgotten.

He listens with close interest as I describe the resources now available to performers, from advocacy group Free Speech Coalition to the union Adult Performance Artists Guild and the mental health resource center Pineapple Support, among others.

We chat about Probst having to come out to those who only knew him as a musician about his abusive childhood, his emancipation at 17 and his career as a sex worker, entrepreneur and beefcake pinup star.

The memoir’s publication has uncovered faultlines that Probst always suspected ran beneath many of his relationships, but he sees a larger storyline at play. It has engendered a fierce empathy for past and present adult performers and sex workers who are just trying to make a buck and save for the future.

“It’s bigger than that,” he muses, when I query him about societal bias against gay men and gay adult performers, particularly men like Probst whose fluid sexual identity challenges staid notions of “masculinity.”

“It’s more about a change in America’s value system,” he notes. “I had a lot of friends — I don’t consider them ‘friends’ — who didn’t even know me that well, growing up. I disappeared when I was 12 years old and didn’t show back up until I was 17. I was in the system. I never saw the outside world. So how all these people even remember me is remarkable in itself.

“Where I come from is like ‘Kentucky in California’ — Bellflower and Lakewood,” he continued. “My point is [friends] were constantly saying stupid, idiotic things… ‘hate this, hate that.’ When I gently started to inform them that maybe, possibly they were mistaken, they all went off and went crazy.

“So that’s a long-winded answer to say that it’s not just the gay part … something we can take away is to fight back as hard as they fight,” Probst added. “The morons fight [to defend] their stupidity harder than smart people fight for the benefit of everybody.”

I explain the mission of XBIZ and the amount of space I have for our story. He’s a longtime businessman and entrepreneur; he knows the score. He urges me to make room in our story for a specific number: 146.

“One hundred forty-six of my friends died,” he says. “It started in 1982 when I was released from the system. And all of a sudden all of these young guys were dying in the bushes. This was before they kept count or anything. I didn’t even know what they were dying from until a man educated me about this ‘gay cancer’ going around. But there was no divide in America. There was bigotry, And there were also subjugated homosexuals who were in the closet and fighting for funding [for disease research] and eventually they died of AIDS [too]. So our own people were part of the problem back then. But there wasn’t this kind of divide we’re seeing now.”

He’s troubled by a vicious schism — right or left, Republican or Democrat, black or white — that he fears is leeching empathy from the people he needs to listen to his story and to remember his friends.

We find common ground in our shared mission to record and contextualize the stories of adult performers, particularly those of gay adult. Many of the industry’s founders — those who were not cut down by HIV — have been lost to old age and infirmity.

But Probst explains he didn’t begin writing his memoir with that particular agenda in mind, not at first.

“I started the book just to get it out. I’m 56 now; I started it in my 40s. It was to shout it out to the world and let them know the truth about those years and the hypocrisy of people — my point was to try and get somebody’s attention,” he says.

But he quickly realized, as he combed through his memories and peered at faded photographs, that almost nobody remained who could also bear witness to those years.

“You’ve got the right person,” he tells me. “I knew almost everybody who was nobody — boys who were just walking down the street and got asked to be in films, I knew ’em all. I knew the directors, all those guys. Writing the book became something bigger than me just getting out my story. I am focused on making sure that none of these guys are forgotten. They don’t deserve mocking or derision. Everyone counts or no one counts.”

Somewhere along the line, Probst decided to start writing and publishing his own obituaries for his friends. His hope is to insert a new narrative into the public waters of the internet; most of the top stories about these long-lost men are simply a plain recitation of their deaths.

“I’ve written 20 already. I write in such a way to let people know they had gifts. They were more than a gay porn star,” he says. “All these people who say to me now, ‘Well, at least you’re not a fag, blah, blah, blah.’ I grew up with them, all those hillbilly types; they looked up to me because they thought I was a rock star. I made it in the music business. I did very well.

“I took a big chance — for me, it was a big risk because I liked some of these guys — when I turned around and changed the tune on them and told ’em what [the memoir] was really about,” he explained. “And I watched who unfriended me. I don’t care anymore what they think. I just don’t give a fuck. As long as my wife is okay, and my son supports me, I don’t care.”

I share with him a few of my favorite anecdotes collected from dozens of interviews over the years and he is particularly struck by an observation that so many civilians — that is, those who may consume adult content but have only observed the industry from the outside — regard these stories as fantastical fairy tales with no basis in everyday truth. Why? Blame sexphobia and the virgin-whore syndrome, blame self-loathing homophobia, blame a deep-rooted misogyny and puritanism. Take your pick.

“I really do think my book shakes up that idea. Why would I write a book when I don’t need to? Why would I tell on myself?” he says. “Why would I do all that? It only hurts me in the field that I’m in [now]. It seems to have blown up because I was honest. I told the truth. Why would I lie and make all this shit up?

“There’s no way you can!” he continued. “When I first started writing, I thought, ‘Boy, this is gonna be fuckin’ embarrassing.’ But I got to tell the brutal honesty; I just got to get it out. That’s a long-winded way of saying to you, ‘I get it.’ But this one, they believe. They believe it.

“It’s a mission of mine,” Probst concluded. “It’s a definite mission to make sure my friends — and I’m talking about my days on the streets, guys nobody knows about, guys that aren’t included in the statistics — are remembered. I really feel a kindred spirit right now. We’re on the same page. Don’t let these guys be forgotten.”

Mayotte: Musings Of A Narcissist: A Survivor's Story is available now online and on Amazon.

Image: Courtesy Kurt Deitrick