CANNES, France — Penthouse International Pictures will premiere an “entirely re-imagined” version of the 1980 erotic cult classic “Caligula” at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

The news was confirmed to XBIZ by Thomas Negovan, producer of “Caligula — The Ultimate Cut.” Negovan has been helming the project for the past four years, working with rights-holders WGCZ and New Orleans-based Penthouse Global Licensing/Kirkendoll Management.

“Caligula — The Ultimate Cut” will be brought to Cannes by Paris-based indie film sales company Goodfellas. Bac Films will release the film in France.

Known as “Caligula MMXX” before the COVID pandemic delayed its unveiling, the new version was painstakingly assembled by Negovan and his team.

A video describing the restoration of the original footage was released by the filmmakers last month.

Negovan told XBIZ that “Caligula” star Malcolm McDowell “has said for 40 years that the edit that was released in 1980 bears no resemblance to the movie he and the other actors believed they were making, and that he knows that despite what the world got to see, they had made a good film.

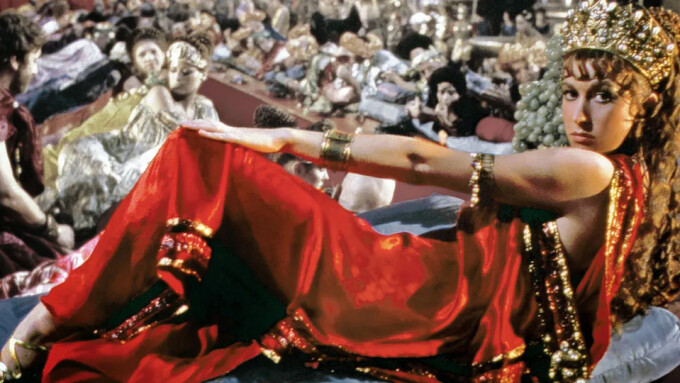

“I’m excited that, after being the stuff of legend for decades, an edit that shows the movie as it was originally filmed will premiere this month,” Negovan added. “And the world will see that he was right: Helen Mirren is radiant, McDowell is at the peak of his powers, and it’s opening a time capsule to see them in footage no human eyes have seen.”

Negovan, who also heads the Century Guild art gallery, said he felt humbled and honored that the Cannes festival was impressed enough with his team’s work to make the movie an official selection.

An Erotic Cult Classic Reborn

In 2021 Negovan described to Fangoria the surprise Penthouse’s new owners experienced a few years ago, when they realized they had also purchased a warehouse that housed all of the surviving material from the beleaguered “Caligula” production.

“It was like the ending of ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark,’” he said. “Huge stacked boxes of original camera negatives, 11,000 black-and-white photos, 16 mm footage of everything that happened behind the scenes. I knew that with this material we could find out if Malcolm was telling the truth. There was incredible acting in those reels. More interesting than the film itself is the story of the making of the film. Honestly, looking at how it’s shaping up, I don’t think there’s a single frame from the original that is in our new version.”

Negovan’s restoration team had to somehow reconcile the contradictory multiple visions of screenwriter Gore Vidal, director Tinto Brass, and producer and Penthouse mogul Bob Guccione — a collision that ultimately doomed the film when it was eventually released in 1980.

One of the reasons the film was so controversial in 1980 was that acclaimed writer Gore Vidal disowned the final film. An expert on classical Greece and Rome, Vidal faithfully based his screenplay on the writings of Roman author Suetonius, but investors demanded that more explicit sex scenes be edited into the carefully plotted narrative.

Suetonius described Caligula’s reign as an orgy of violence and corruption, presided over by a completely unstable leader prone to sudden mood swings and tyrannical stunts. Caligula’s shenanigans depicted in the film include appointing his horse as a senator, building a brothel and forcing the wives of rival senators to work there, executing people on a whim with elaborate torture devices, disappearing from the palace without warning and, most infamously, crashing a friend’s wedding night to deflower the young bride before fisting the groom.

Negovan noted that original director Tinto Brass’s style in the theatrically released edit would have been too singular to emulate, necessitating a different strategy.

“It’s such a clear personal style and I felt it would be disrespectful to try to recreate it inauthentically,” he explained. “To me, the most respectful approach to this story was not to go the avant-garde cult film approach, which is what Tinto would do, but to acknowledge its incredibly powerful narrative that Gore Vidal etched out — to try not to impose any opinions beyond service to the intended story, because it’s not our art.”