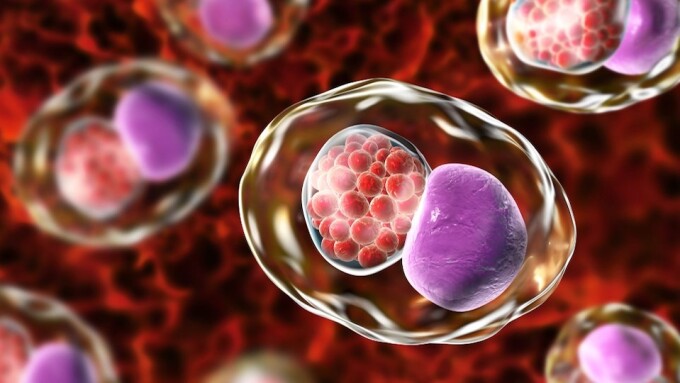

LONDON — Researchers from Imperial College London and the Statens Serum Institut (SSI) in Denmark have announced a breakthrough in a new genital-chlamydia vaccine.

Although still in its early stages of development, the team has reported that the first-ever human trial of the vaccine yielded results that would suggest it to be both "safe and effective."

As per the recently published study in The Lancet medical journal, a double-blind, randomized trial was conducted with a group of 35 healthy women ages 19-45 years old; five of them received a saline placebo while the remaining 30 women received one of two vaccine variants.

According to the researchers, both vaccines successfully triggered an immune response, one version more so than the other, and yielded minimal side effects, the most common of which was injection site discomfort.

One of the study's co-authors, Professor Robin Shattock, Head of Mucosal Infection and Immunity at Imperial College London, shared that a vaccine "can't come soon enough."

As the most common sexually transmitted bacterial infection worldwide with a staggering 131 million documented new cases per year, chlamydia is still a "major global health burden," as per a commentary linked to the study.

Although easily remedied with antibiotics, chlamydia frequently goes undetected and, if left untreated, can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and in severe cases, infertility. It can also increase one's susceptibility to other infections, including HIV.

While a report from Time magazine noted that the study did not test the vaccines against chlamydia in this early trial, researchers concluded that the stronger of the two vaccines "holds promise" for further development.

The next step, according to a Science News report, would be to test the vaccine's efficacy in preventing an infection, a process which would involve "at risk" volunteers.

Should the vaccine pass through clinical trials and be approved for use, Shattock expects that it would initially be targeted to girls around age 11-12, similar to the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine.

“In the same way that HPV is a sexually transmitted infection, but people are motivated to get vaccinated because they want protection from cancer, we would anticipate that this would be positioned as a fertility vaccine,” he said.

For now, Shattock says the team remains "cautiously optimistic" and hopes that the world will see a genital-chlamydia vaccine become commercially available in the next five to seven years.